ART: Auction helps promote pedal power

A number of years ago, a fire broke out at a storage garage where many Edmontonians who owned high-end sports cars or other vintage automobiles kept them for the winter. The blaze destroyed some very expensive vehicles, and as you can imagine, their owners were terribly upset.

But the car that Edmontonians cared most about — judging by the attention it received in local TV newscasts, at least — was a rusty old Porsche from the late 1970s. The reason? It was once Mark Messier’s car, given to him by former Oilers owner Peter Pocklington as a signing bonus.

Edmonton has a lot going for it these days, but the fuss that was made over that car was a reminder of how this city has a peculiar way of living in the early 1980s. It’s understandable. The Oilers were winners and SCTV, which was made in Edmonton, got picked up by NBC. The plummeting oil prices that hit Alberta like a thunderbolt later in the decade hadn’t happened yet, and the whole city was riding a petroleum wave that rolled along bigger than the ten-footer in the opening credits of Hawaii 5-0 (the OLD Hawaii 5-0, kiddies).

Yet there was a strange group of people at that time who thought the way to really improve the place would be to have fewer cars on the road. They were urban cyclists, and they formed Edmonton Bicycle Commuters.

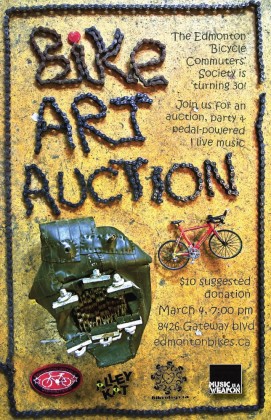

Thirty years later, they’re still around. And after years of their members being confused with everything from Lance Armstrong-like racing cyclists to people who are too poor to afford cars, EBC is celebrating its birthday with a bicycle art auction that expresses the urban riders’ own form of cycling culture.

“It’s pretty open. Our qualification is that it had to have a bike focus, or be made out of bicycle parts or recycled bicycle products,” Anna Vesala of EBC explains about the types of pieces that will be in the auction, which will be on March 4 at the Old Strathcona Performing Ats Centre, 8426 Gateway Blvd.

Artists will get the proceeds from the sales, but in order to take part, each artist has selected a percentage of the selling price that will be donated to EBC.

Submissions so far include everything ranging from artistic bicycle photography and clothing to a table made from a bicycle wheel.

“This is our first of this event, so we weren’t sure what we’d get. I’m very excited about what we did get,” Vesala says.

Katrina Olson has submitted several pieces of jewelry that she made from recycled bike parts. She’s been making jewelry since she got a bead kit when she was still a kid, and only recently began making items out of bike parts.

The bike jewelry started when she became a cyclist, she explains. And that happened when she was living in Winnipeg and a travelling cyclist from Edmonton pedalled through town. She moved to Edmonton to live with him, and where he saw parts for a bike, she saw materials for bracelets, ear rings and necklaces.

Old chains work really well for jewelry, Olson says. Spokes are good, too, because they can be easily bent when heated.

“I like it because it’s something old with something new. I try to make it pretty like regular jewelry that someone would wear rather than just because it’s recycled,” Olson says.

“It’s a way to associate with cycling outside of cycling, to say, ‘This is what I do.'”

Neither Olson nor Vesala are as old as EBC, but both have been around long enough to see a sharp rise in the number of people riding bicycles in cities, particularly in the last five years. Naturally, the new numbers have sparked a culture, which in turn produce s art.

s art.

“To me, it’s anything that promotes or celebrates anything on two wheels,” Vesala says of bike art.

“I don’t know, I’m not really an artist myself,” she continues. “I think there’s a definite admiration of the beauty of the structure (of a bike) itself.”

Vesala says that as more people ride in cities, it becomes more socially acceptable. But as urban cycling becomes more mainstream, what will happen to its art? Can it survive being cool?

After all, it’s hard for a culture to keep its edge if social acceptability leads to urban cyclists in Coca-Cola ads.

“Cycling culture is still unique now. If it becomes cool, I think the culture would dissipate a bit,” says Olson.

“It would be good if more people were on bikes like in European cities where so many people ride. In the end it would probably be a good thing if it made cycling more popular.”

Related articles

- 2011 North American Handmade Bicycle Show: Best in Show awards (velonews.competitor.com)

- Pedal Powered Community (dothegreenthing.com)

- The most popular cycling stories in 2010 (eta.co.uk)