Obsolescence, photography, death and Polaroids

How long has it been since you smelled the chemical aroma of a Polaroid photo fresh out of the camera? Ten years? Twenty?

How long has it been since you smelled the chemical aroma of a Polaroid photo fresh out of the camera? Ten years? Twenty?

Can you even still buy the film? (Yes and no. We’ll get to that.)

Polaroid photographs generally weren’t considered art. The film and the print were the same thing so you couldn’t alter, crop or enlarge them. The colours were always a bit weird, too.

Still, Polaroids were always sort of special. Instant photography wasn’t cheap so you usually only took them at parties or barbecues, and even then you only took a few so the kids would have pictures to look at right away, while the rest of your pictures were taken on a regular camera.

Polaroids were also the only way amateurs could take their own dirty pictures because you didn’t have to develop them to a lab where, at the minimum, you’d receive smirks from the shop staff, or worse, you could get arrested.

So when local amateur photographer Alex Hindle stumbled upon several large, long-expired stocks of Polaroid film, he decided to use them for something special.

So when local amateur photographer Alex Hindle stumbled upon several large, long-expired stocks of Polaroid film, he decided to use them for something special.

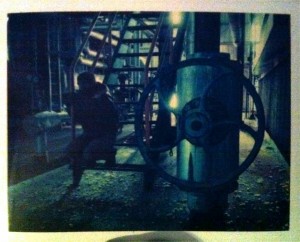

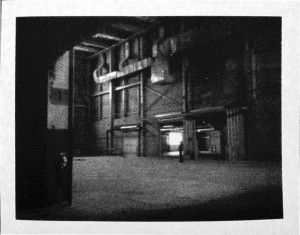

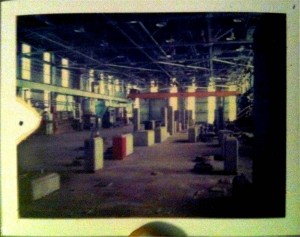

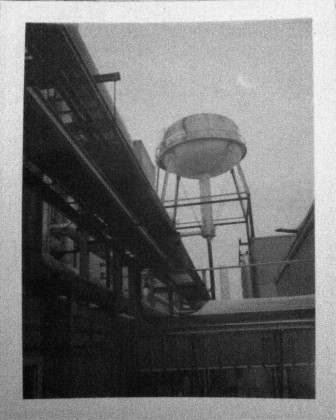

The idea was that he and a friend, Leila Sidi, would take pictures inside an abandoned chemical facility on the outskirts of Edmonton.

“We wanted to use this dead format to document this dead subject,” explains Hindle.

Hindle got his first 20 boxes of colour film, which is good for 200 photos, for $50 at an Alberta government surplus auction. He later bought another 10 boxes of high-speed black-and-white film through Kijiji from the University of Alberta Hospital.

The government’s colour film had likely been used for shooting pictures for identification cards and badges, Hindle says. He suspects the hospital used its black-and-white film for some sort of imaging. It’s very sensitive — 3200 ISO.

He found a Polaroid Reporter camera at Classic Camera in Edmonton, and then acquired some other Polaroid cameras from friends.

He found a Polaroid Reporter camera at Classic Camera in Edmonton, and then acquired some other Polaroid cameras from friends.

“It was big and black and folded into a plastic case,” Hindle says of the camera. “I didn’t know how to load it properly so I wasted a couple of packs.”

Sidi, who studied photography at NAIT about 10 years ago, had prior experience with Polaroids. When setting up a shoot, she says students were trained to take a Polaroid of their subject to get an idea if they’d gotten the lighting right.

But beyond their obvious utility, Sidi says Polaroid pictures offer something more.

“It has a unique aesthetic — desaturated colours, the size, even the white border are all characteristic of Polaroids,” Sidi says.

“Depending on the temperature, you can get vibrant colours.”

“Depending on the temperature, you can get vibrant colours.”

Polaroid film was still available for sale in Edmonton, even in supermarkets, as recently as a few years ago. But in 2008, Polaroid announced it was ending production of film at its last two facilities in The Netherlands and Mexico.

The only new film that works in Polaroid cameras is available for order in limited quantities, produced by some former Polaroid employees under the banner of The Impossible Project. Expect to pay afficianado prices.

Digital photography, which is not only instant but can also be emailed to all your friends and family, has for the most part finally replaced Polaroids.

“I’m not of the belief that digital photography is bad or evil, but there is a tendency to take pictures and never print them. With film photography, you have an artifact,” Hindle says.

“My interest in the Polaroid has nothing to do with the fact that it’s instant. It’s that it’s obsolete and inalterable.”

There was a sense of ceremony to taking Polaroids. If you had the OneStep, for which actor James Garner did commercials (there’s an example below), you pressed the button and your print spat out the front. Then you and the people whose pictures you’d taken gathered around and stared as an image magically materialized over about 60 seconds within the white-framed border.

If you had a Polaroid 600 or similar model that had an accordion-like folding body, you pulled your fresh print out the side of the camera, placed it between two metal plates and then squeezed the print under your armpit to keep it warm while it developed.

And when you saw the pictures, it wasn’t like you were looking at your vacation snaps that you’d taken last week. It was of the room that you and your guests were still in, with the birthday cake still on the table. You got the feeling you were standing in history.

Hindle says that since his film stock is so old, the colours are even more distorted (and some a little more so in our scanning attempts), which adds to the sense of decay in the pictures of the industrial facility. The high-speed black-and-white film, meanwhile, produces slightly hazy images which make the large spaces filled with stairways and pipes appear ghost-like.

The hope, Hindle says, is that he and Sidi will have a little show somewhere to display the pictures. Sidi is also taking regular photographs of the chemical plant, so there will also be prints that are larger than Polaroids.

“People think it’s kind of quaint. It’s not a film people understand,” Hindle says of Polaroids.