Reading a right at Edmonton Remand Centre

Imagine if you had weeks, or months, or possibly years to go by, sitting in a tiny room with little else to occupy your time except read – but your selection of books was bought for $10 per box on the last day of an Edmonton Public Library book sale.

Imagine if you had weeks, or months, or possibly years to go by, sitting in a tiny room with little else to occupy your time except read – but your selection of books was bought for $10 per box on the last day of an Edmonton Public Library book sale.

Books for prisoners at the Edmonton Remand Centre used to be purchased from local second-hand bookstores like Wee Book Inn, but switched recently to buying in bulk from the library because it saves money.

One former inmate, who doesn’t want his name used because he’s cleaned up his life and is now looking for work, says he doesn’t blame the Remand for scrimping on books. You can’t smoke in the jail, he says, and some inmates use books to make cigarettes.

“I once took a hit off a cigarette made from pages from the Bible that were soaked in whatever they could scrape from a nicotine patch,” he says.

Chris Hay, executive director of the Alberta John Howard Society, says it’s frustrating that books seem to be considered a luxury for inmates. He says eliminating privileges like TV, which is often debated, or supplying inmates only with the cheapest books could harm their chances for rehabilitation and sends a message that society doesn‘t care about them.

“I don’t like offenders any more than the next person. They’ve hurt someone,” Hay says. “But if you kick a dog enough times it will bite you. A human being is no different. TV is a privilege but I don’t think books are a privilege – they’re a right.”

Inmates at the Edmonton Remand Centre are locked up for between 18 and 21 hours per day with limited access to recreation or other activities, according to a 2010 report by Queen’s Bench Justice Richard Marceau. The centre was built for 340 prisoners while they await trials but it regularly houses closer to 800. Marceau’s report slammed the facility for conditions that ranged from providing stained and used underwear to inmates, to racist behaviour by guards. The report stemmed from a Charter challenge that was launched by a group of alleged drug gang members in 2001 – and among the complaints in the original challenge was a lack educational and media resources.

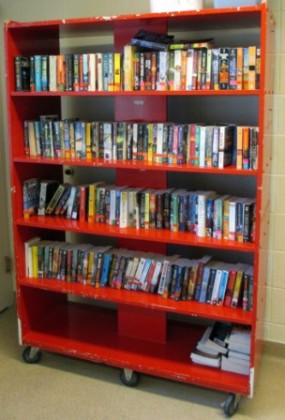

The Edmonton Remand Centre has about 2,000 books which are circulated to prisoners on carts that are wheeled to the cells. There is no list or records of what’s being read. Books get replaced as soon as they appear too worn for circulation. A photo (right) of a shelf of books that was supplied to Gig City by staff at the facility shows at least a few recognizable authors, like Tom Clancy, Danielle Steel and Stephen King while others aren’t so familiar.

The Edmonton Remand Centre has about 2,000 books which are circulated to prisoners on carts that are wheeled to the cells. There is no list or records of what’s being read. Books get replaced as soon as they appear too worn for circulation. A photo (right) of a shelf of books that was supplied to Gig City by staff at the facility shows at least a few recognizable authors, like Tom Clancy, Danielle Steel and Stephen King while others aren’t so familiar.

Sheineen Nathoo, who coordinates volunteers for the library sales, says just because the books are purchased on the final day of a sale doesn’t mean they’re no good. Boxes are continually being brought out of storage, many filled with popular titles, and are placed on tables. Anyone who fills a box at the end of the sale should theoretically have as good a selection as would be available on the first day. An Edmonton Remand Centre staff member bought boxes and boxes of books at a library sale in 2011. The Remand also accepts donated books, which can be dropped off at the front reception desk. Pornographic or hateful material is prohibited, as are hardcovers because inmates have been known to make weapons out of them. (Legal books are the exception.)

Solicitor General and Public Security spokesman Jason Maloney maintains buying that books from the library sales is cost-effective, although he admits the possibility the selection could be limited on the final day.

“You might have some people who say they don’t deserve books. We don’t take a side either way.” he says. “We just supply the books and it’s up to the inmates whether or not they want to read them.”

Rachel Posch, principal of the adult transition learning centre with the Edmonton John Howard Society, says what’s really lacking in jails are books at a lower reading lever than are normally written for adults. Literacy levels in prisons are lower than the general population, and she says it would be helpful and motivating for inmates if they could get something beyond children’s literature. Resources are limited. “It’s getting better but it’s been a problem,” she says.

It’s not hard to find testimonials to the benefits of reading in jail. In southern Ontario a group called Books to Bars organized donations of books to prisons and remand facilities in the London and Hamilton areas, following cuts to library funding in jails. The group’s website includes notes of thanks that were typed by inmates in the Hamilton Wentworth detention facility, where prisoners are held while awaiting trial.

Inmate Mark G. wrote: “We are all human and we all make mistakes! Books are so instrumental in my personal journey, and have been guide posts to a new positive way of life. I thank you from the bottom of my heart.”

A 32-year-old inmate named Jason, meanwhile, wrote that he’d been in custody most of his adult life and that reading helped him escape: “Maybe all of us here deserve to be here, but having proper reading material and just something to make our minds change, maybe us inmates may not find ourselves here time and time again.”

A replacement for the Edmonton Remand Centre is slated to open this fall. Maloney says it won’t have a dedicated library but that shelves for books will be located in the “living units.”

The former inmate who smoked the Bible cigarette says the longer-term inmates are the ones who read the most. Some inmates can spend years in the facility.

“Those guys just give up watching TV and read,” he says. “And don’t interrupt them.”