ART: Les Automatistes still making modernist waves today

Posted on July 1, 2012 By Stuart Adams Culture, Front Slider, Visual Arts

A painting by Les Automatiste artist Jean-Paul Riopelle may have sold for $2.2 million at a recent auction in Paris – but it is the work of the group’s driving force Paul-Emile Borduas (above) that really stands out in a new exhibition at the Art Gallery of Alberta.

The Automatiste Revolution: Montreal 1941-1960 exhibit, up until mid-October at the AGA, features half a dozen other potentially pricey Jean-Paul Riopelles. You’ll also have the chance to see a painterly chronicle of “Les Automatistes,” the movement that shaped and formed Riopelle, among others, and which generated what has become Quebec’s most notable manifesto, the 1948 publication Refus Global – Total Refusal.

No trip to Paris required.

No two ways about it, Les Automatistes shook Quebec’s art world after World War II and wound up making the kind of international waves that are still reverberating – both among Quebec artists, but also at auctions such as recent one at Christie’s. While Riopelle became the most well-known artist to come out of the group, Paul-Emile Borduas was the progenitor behind the movement. There are the more than 50 other works by painters who were also part of Les Automatistes, along with writings, photographs and a video representing the other disciplines.

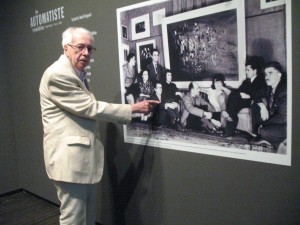

A little historical context helps appreciate the group’s origins and activities. Marcel Barbeau (right), the last surviving member of Les Automatistes, was a student of Borduas’ at the École du Meuble during those times and, now, 87, was in Edmonton for the opening of the exhibition.

A little historical context helps appreciate the group’s origins and activities. Marcel Barbeau (right), the last surviving member of Les Automatistes, was a student of Borduas’ at the École du Meuble during those times and, now, 87, was in Edmonton for the opening of the exhibition.

“He was a kind of ‘mage’, something of an artistic prophet,” Barbeau says of Borduas, whom he studied under while still a teenager.

At the time, the cultural climate in Quebec was stifling. The Duplessis government and the capital ‘C’ Church enclosed artistic expressions allowed in the province in dual iron fists. The École des Beaux-Arts was the “establishment” school where art students toed the cultural line. However, by the early ‘40s, Borduas had gained a following at the École du Meuble, which originally focussed on furniture design. He had been to Europe himself, but was also in contact with other artists who brought abstract art back from across the ocean.

The École du Meuble became a magnet for the bad boys and girls of Quebec’s art world, those who wanted to think for themselves and explore new ideas through the arts.

“There was a competition between the École des Beaux-Arts and the École du Meuble,” explains Barbeau. “The École du Meuble wanted to be more progressive. Many students move to the École du Meuble to study with Borduas.”

Roald Nasgaard is the AGA exhibition’s curator and talks about the movement. “It arose out of artistic visions,” he says, “and the artistic visions took on political overtones.”

The exhibition notes underscore the group’s significance how their manifesto “became one of the pillars of the Quiet Revolution, a period of intense change in Quebec. Refus Global was an anti-religious and anti-establishment manifesto – one of the most controversial artistic and social documents in modern Quebec. The Automatistes were not solely painters, but also included dancers, playwrights, poets, critics, and choreographers. After 20 years of challenging the politically and religiously repressive Quebec society, the Automatiste group disbanded in 1960 after the death of Borduas.”

Borduas, as the leader of the movement, shines in this show. Riopelle, who died in 2002, is well-represented by his half dozen pieces, as are other members of the movement (Barbeau has a particularly fine canvas), but of the 20 or so, Borduas’s works dominate. They track his explorations, from the early inception, through to his last years. As such, he is a mature painter exploring and evolving, while the younger artists are simply emerging. The distinction is palpable and the opportunity to walk through time with Borduas and the other Automatistes will make you glad to stay home and take a trip to the AGA.