Oilers hero sour on Lance Armstrong memorabilia

Posted on November 1, 2012 By Rob Drinkwater Culture, Features, Front Slider, TV and Radio, Visual Arts

Georges Laraque owns three limited-edition replicas of the Trek bicycles that Lance Armstrong rode during his latter Tour de France victories, two of them autographed, one even decorated with 23-karat gold frame panels – and the former Edmonton Oiler can’t even stand to look at them anymore.

“I got sick to my stomach because I didn’t want to endorse someone who didn’t just cheat – he lied,” Laraque says.

Since the International Cycling Union stripped Armstrong on Oct. 22 of all seven of his Tour victories from 1999 to 2005, Laraque says he wants his money back.

“Those bikes are a lie, a joke. How could the Trek team not know?” Laraque asks about the cheating that was alleged in a report released in early October by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency.

“(Trek) sold those bikes because it was supposed to be the bike of a winner,” he continues. “I might even take legal action to get them to take them back.”

The bikes, he estimates, cost about $12,000 each. A limited edition 2005 Madone SL Live Strong – the final bike that Laraque bought – was one of only 600 made.

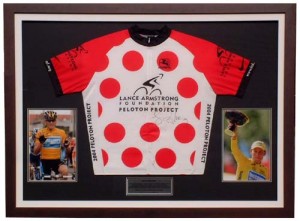

Cycling fans all over the world have been looking uneasily in the last few weeks at their framed, autographed, and limited edition collector’s prints, jerseys and other memorabilia of the now-disgraced cyclist as he battled in various stages of his record seven Tour de France wins. In Edmonton, there are art shops that sell prints of paintings of Armstrong’s past. One framing shop in the city shows on its website an example of work they did for a client, where one of Armstrong’s autographed yellow jerseys is framed along with a photo of the cyclist.

Laraque, who was speaking by phone from Montreal where he now lives, bought the first of the limited edition bikes in 2003. Unlike many well-heeled Armstrong fans who simply hung the commemorative bicycles on their walls like art, Laraque rode all three of his bikes and even competed in local triathlons during the hockey off-season. They were strong carbon-fibre frames, which Laraque said he needed because he’s bigger than the average cyclist and he’d damaged an earlier bike he’d owned.

Laraque, who was speaking by phone from Montreal where he now lives, bought the first of the limited edition bikes in 2003. Unlike many well-heeled Armstrong fans who simply hung the commemorative bicycles on their walls like art, Laraque rode all three of his bikes and even competed in local triathlons during the hockey off-season. They were strong carbon-fibre frames, which Laraque said he needed because he’s bigger than the average cyclist and he’d damaged an earlier bike he’d owned.

There was more to them than just utility. Laraque says he also bought jerseys of the teams Armstrong rode for over the years. He’s got a mountain of merchandise from “Livestrong,” the charity for people affected by cancer that Armstrong founded and headed until stepping down as chairman a few weeks ago.

Laraque used to buy hundreds of yellow Livestrong bracelets at a time to give away. He says he would have even been among the people who paid to ride with Armstrong when the cyclist made visits to Edmonton, but couldn’t because it was too close to the Oilers’ training camp.

“The reason I got into cycling was because of Lance Armstrong,” Laraque says. “I wanted to be the black version of Lance Armstrong.”

Trek dropped Armstrong as a sponsor on Oct. 17, though the company stated it would continue to support Livestrong. According to an Oct. 18 report on www.cyclingnews.com, Trek spokesman Bill Mashek said that Armstrong still has a very small share in Trek that was granted to him in the early 1990s. Mashek said the share was less than one-quarter of one per cent.

After the report from the US Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) came out on Oct. 17, Trek issued a statement “terminating our longterm relationship with Armstrong.”

The effect that the controversy will have on the value of Armstrong memorabilia is unknown. Rich Miller, editor of SportsCollectorsDaily.com, was quoted in the “Business and Money” section of Time’s website on Oct. 18 that higher-end Armstrong pieces could lose half their value.

Optimists suggest that scandals may have the opposite effect on memorabilia and could jack the value higher. But an owner of an auction company who is also quoted in the Time story notes that the value of Barry Bonds and Mark McGwire merchandise has plummeted following baseball’s steroid scandal. Sammy Sosa cards barely sell at all, the owner says.

Optimists suggest that scandals may have the opposite effect on memorabilia and could jack the value higher. But an owner of an auction company who is also quoted in the Time story notes that the value of Barry Bonds and Mark McGwire merchandise has plummeted following baseball’s steroid scandal. Sammy Sosa cards barely sell at all, the owner says.

Laraque says that for years he didn’t believe the rumblings and allegations that Armstrong was doping. He says he hated Tyler Hamilton, one of Armstrong’s former teammates who accused him of doping, because he thought he was just bitter about having been caught himself. He says he thought people were running Armstrong down because he was arrogant.

But the USADA report was too much. Armstrong’s supporters claim some of the former teammates whose testimony it contains were coerced and threatened with probes into their own doping abuses. The trouble is, there’s just so many of them.

“There were so many things that I’d heard over the years. I didn’t think he could be taking drugs,” Laraque says. “Now he’s in a position where he has no choice but deny it. He’s still lying about it.”

In a bike shop called Mellow Johnny’s that Armstrong co-owns in his hometown of Austin, Texas, paraphernalia of the business’s famous founder still hold a place of prominence. (“Mellow Johnny” is Armstrong’s term for “malliot jaune,” which is “yellow jersey” in French.) Craig Staley, the store’s general manager, told Fox News in Austin that Armstrong still has a large fan base in the city for his work with Livestrong.

Laraque, however, says he’s not even keen on Livestrong anymore, following several negative stories this past year. One of those pieces includes allegations in the Wall Street Journal that Livestrong used one of its lobbyists to argue Armstrong’s case to a U.S. congressman. An article that ran in Outside in January questioned whether advertising for Livestrong was indirectly being used to bolster Armstrong’s image.

Charity ratings organizations reportedly give Livestrong high ratings for the amount of money it directs to programs as opposed to administration.

As for Laraque, he says he doesn’t even ride anymore – he’s switched to running. The bikes and all the other Armstrong memorabilia he owns used to make him feel good. Not anymore.

“I have lots of Livestrong stuff,” he says, “but all of it is garbage.”