COMICS: Gritty ’60s, lousy ’80s fuel super-powered noir

Posted on December 7, 2012 By LH Thomson Features, Front Slider, Visual Arts

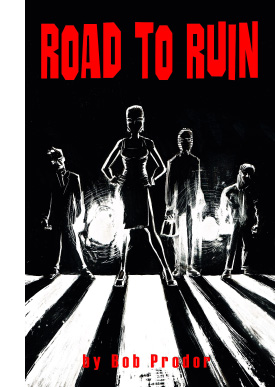

If the ’80s hadn’t sucked so very, very much, it’s quite possible Bob Prodor wouldn’t have drawn his dark, expressive noir crime comic Road To Ruin.

If the ’80s hadn’t sucked so very, very much, it’s quite possible Bob Prodor wouldn’t have drawn his dark, expressive noir crime comic Road To Ruin.

The Edmontonian’s 128-page graphic novel, featuring a gang of Rat Pack-style crooks in the 60s with “limited” superpowers, is on sale now, published by Rosencrantz Comics. There will be a local launch for the book Dec. 14 at Zenari’s, 10180 – 101 Street.

So what do 60s Rat Packers have to do with the 80s and Prodor? The 80s are big these days, which doesn’t surprise any of us. The ’60s were big in the ’80s, and the ’70s were big in the ’90s, and so it goes.

But there’s a different between how we love the 80s and how we loved the 60s, and that had a broad cultural impact, particularly on comic books: the latter had Vietnam, so even when we were nostalgic for it, we remembered there was another side to the coin that actually led to all that peace, love, understanding and vast marijuana consumption.

The 80s, on the other hand, are remembered via the filter of films like “Hot Tub Time Machine” and “Take Me Home Tonight”: everyone parties all the time, everyone loves the same iconic songs and everyone dresses in enough neon pastel to blind a Vegas chorus line of drag queens.

In reality, the ’80s made the stifling authoritarianism of the early ’60s seem like summer camp. The ’80s gave us “Just Say No” (to drugs, sex, education, unions, anything communal at all), “Greed is Good,” “Where’s the Beef.” So some of us remember the reality: the ’80s sucked.

Comics began to reflect that bleak, gritty outlook. If the ’80s hadn’t been so bleak, noir fiction might not have made a roaring comeback, with people rediscovering writers like Jim Thompson (The Grifters, The Getaway, The Killer Inside Me) and comic books recognizing an adult market, really for the first time.

Until the ’80s, comics were mostly kids’ stuff. The self-imposed Comics Code authority was used by the industry to censor itself, after McCarthy-style hearings in the 1950s into lurid and violent adult comics threatened the entire industry. But in the early ’80s, comics like “Swamp Thing”, “Cerebrus The Aardvark”, “Badger” and “Ronin” decided it was time to write comics for adults again.

And that’s how Edmonton’s Bob Prodor wound up a comic book artist and writer. He was in a local Guardian drugstore in Crestwood and he saw a copy of the Frank Miller-drawn “Wolverine” four-part mini-series on the comic book rack.

It was the first time Wolverine had been featured as a solo character, and he went to Japan, fought Samurai. “It’s like he was beckoning you, crouched down on that cover with three claws out in front. And that was it, right there: I was hooked.”

It was the first time Wolverine had been featured as a solo character, and he went to Japan, fought Samurai. “It’s like he was beckoning you, crouched down on that cover with three claws out in front. And that was it, right there: I was hooked.”

Miller became a big influence on Prodor; while he has his critics, Miller’s massive influence on the industry – from the Elektra saga in Daredevil, to Ronin, to the Dark Knight Returns, to Batman Year 1, to Sin City – has come because of his willingness to go dark and to discuss adult themes.

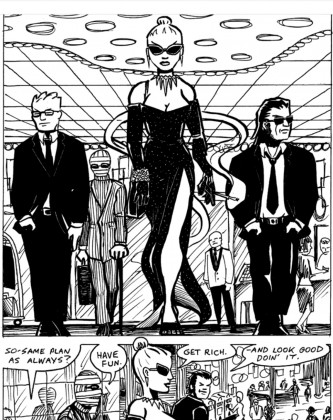

“People have said (Road to Ruin) would be in the same kind of area as Sin City, which I guess is an honest comparison, because I grew up reading Frank Miller. I really wanted that sort of punk attitude.”

Miller’s work was also a product of the decade in which he rose to prominence. The 80s were the decade of the Ayn Rand loving corporate sociopath, the Patrick Batemans of the world. Kids in the ’80s didn’t just smoke weed, they snorted enough coke and took enough speed and acid to lobotomize themselves; they inhaled deodorant and rubber cement through towels. They did anything they could to medicate the reality of the world away. Favorite 80s activity for any suburban kid over age 14? Smoking a joint and laughing at the “This is Your Brain on Drugs” commercial. It was a reaction to the shitty, non-empathetic, small-minded culture they were living in.

Miller’s work was also a product of the decade in which he rose to prominence. The 80s were the decade of the Ayn Rand loving corporate sociopath, the Patrick Batemans of the world. Kids in the ’80s didn’t just smoke weed, they snorted enough coke and took enough speed and acid to lobotomize themselves; they inhaled deodorant and rubber cement through towels. They did anything they could to medicate the reality of the world away. Favorite 80s activity for any suburban kid over age 14? Smoking a joint and laughing at the “This is Your Brain on Drugs” commercial. It was a reaction to the shitty, non-empathetic, small-minded culture they were living in.

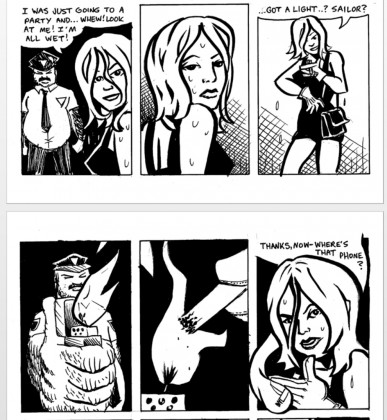

Early on in Prodor’s book, there’s a particularly terrifying – near horrifying – scene. Without spoiling it, neither of the people in the scene seems menacing, but both are terrifying beneath their immediate exterior. Prodor felt the peril in which he’d placed a lead female character required getting permission from his girlfriend. It’s that intense.

His work has that kind of impact because even though his style verges towards the Robert Crumb/indie side, the amazing nuance he gives each character, particularly in facial expression, brings Road to Ruin to life. It was a different approach, treating the comic like a film with as many scenes as are required, instead of following the typical book formula of a limited number of panels.

“When it comes down to it, if all you’re doing is taking your inspiration from other comic books, you’re really not going to do anything new,” said Prodor. “If you look around at what people draw, you can tell who was into Image or who was into another line of books by how and what they draw. You can tell if a guy’s into Wildcat and Youngblood, or Spawn, or whatever. You can see it a mile away if you let yourself be influenced like that. It gets a bit ridiculous; I mean, how much of that stuff do people need?”

Of course, promoting indie work is still a slog with which many artists struggle, and Prodor admits he’s no different. The book has international distribution through Bayeux Arts, but he doesn’t know yet how many stores will pick it up or how it will do; there have been some positive reports already, but he knows it’s a good thing the 128-pager is a labor of love. “It’s hard to blow your own horn, I find. And you really have bug people over and over, which is uncomfortable for a lot of people.”

Of course, promoting indie work is still a slog with which many artists struggle, and Prodor admits he’s no different. The book has international distribution through Bayeux Arts, but he doesn’t know yet how many stores will pick it up or how it will do; there have been some positive reports already, but he knows it’s a good thing the 128-pager is a labor of love. “It’s hard to blow your own horn, I find. And you really have bug people over and over, which is uncomfortable for a lot of people.”

He’s getting some support from local music legend Corb Lund. Lund is a fan of Prodor’s and worked with the artist on his Western Tales comic a few years ago. Now Lund has let Prodor use his song “Your Game Again” for a short promo film for the book.

“James (Davidge, his collaborator) suggested it and as soon as he said it, I knew it was perfect. It just fit.”

– when he’s not writing for Gig City, LH Thomson writes crime fiction.