Punk artist reveals deep roots

Posted on June 6, 2017 By Mike Ross culture, Entertainment, Front Slider, Music, Visual Arts

The Blueberry Bluegrass & Country Music Festival is lucky to own the latest creations from Edmonton artist Spyder Yardley-Jones: a mandolin bigger than a bull fiddle, a towering acoustic guitar and a Brobdingnagian banjo. The fiddle next time.

The Blueberry Bluegrass & Country Music Festival is lucky to own the latest creations from Edmonton artist Spyder Yardley-Jones: a mandolin bigger than a bull fiddle, a towering acoustic guitar and a Brobdingnagian banjo. The fiddle next time.

The heavy plywood sculptures will be paraded around Parkland County in an antique truck before being put on display at the annual bluegrass music event in Stony Plain’s Heritage Park Aug. 4-6.

“They’ll also use them for a beanbag toss thing,” Spyder says. He’s always up for getting kids involved in art.

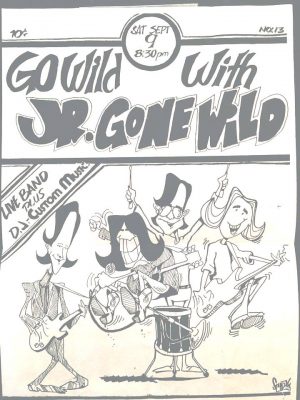

These props are just the latest work in remarkable career that has deep roots in Edmonton’s music scene – particularly in punk rock. Spyder has designed literally thousands of gig posters. Name the local punk band and chances are he’s drawn them.

Son of famed editorial cartoonist Yardley Jones, Spyder came to Edmonton from Montreal in 1981, and almost immediately ensconced himself in the city’s growing punk scene of the time. Montreal was into British punk, he recalls, but “out here it was West Coast hardcore,” like Black Flag. Spyder was into it. “Edmonton had the toughest pits,” he says.

From given-name Paul, he’d dubbed himself Spyder in part to deal with social anxiety disorder only recently diagnosed. “Now I understood why I behaved the way I have been,” he says. “I thought I was losing my mind.” He says it was due to lingering trauma from being severely bullied as a child. Older kids would attack him from behind and beat him up for no reason. He says no one ever helped him.

“When I took on the persona of Spyder in 1980, I looked at it as my rebirth,” he says. “Spyder was not going to be picked on anymore. So when there were fights, it was me in charge. That was back when there were all those white supremacists in town. I got to beat some of them up.”

“When I took on the persona of Spyder in 1980, I looked at it as my rebirth,” he says. “Spyder was not going to be picked on anymore. So when there were fights, it was me in charge. That was back when there were all those white supremacists in town. I got to beat some of them up.”

Alberta rednecks of the time hated punks, and Spyder recalls fights on Jasper Avenue. He tells the old joke, “I was into punk when it was called ‘hey, faggot!’”

Turned out he was neighbours in Edmonton with one Gubby Szvoboda, local punk guru and one-time manager of SNFU. Spyder spotted a DOA poster in Gubby’s window one winter, and so he began writing encouraging messages in the snow – “and that’s how we connected.”

Spyder found his tribe.

“When I went to my first gig in Edmonton, I’d never seen stage diving or thrashing. It was at DOA. And I was standing at the back of the hall, just checking things out, and I just saw people flying around, I went, ahhh, this is it! I’m home.”

All the friends he made were musicians, but since he couldn’t sing or play an instrument, Spyder made a career as an artist. “I’m not rich,” he says now. “I’m poor – but I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

All the friends he made were musicians, but since he couldn’t sing or play an instrument, Spyder made a career as an artist. “I’m not rich,” he says now. “I’m poor – but I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

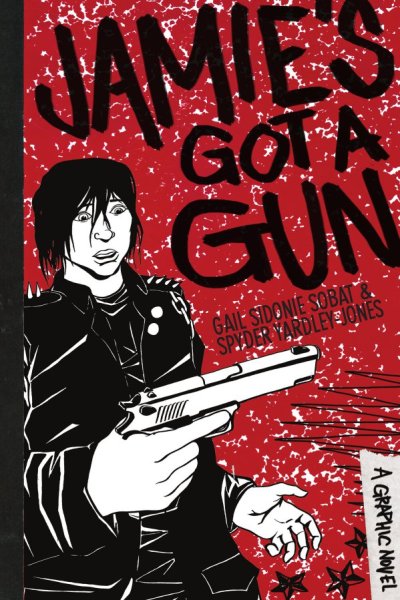

With what could be called “dark” style, his many projects include an award-winning graphic novel called Jamie’s Got a Gun, a series of advertising cartoons to promote tea, and a children’s Halloween book called In the Graveyard. He also followed in his father’s footsteps, drawing sports cartoons for the Edmonton Journal in a series called Jock Strip, and editorial comics for See Magazine and The Edmonton Sun. His boss at the Sun was Graham Hicks, who sometimes didn’t get Spyder’s humour – and would literally write “NOT FUNNY!” across comics he didn’t like.

In more recent times, Spyder teaches art in a series of school residencies. His favourite is the CASA Child, Adolescent and Family Mental Health facilities.

“It’s such an unbelievable facility,” Spyder says. “It’s unbelievable what they’re doing for kids.” He started volunteering, and later earned a permanent annual residency at CASA sponsored by the St. David’s Welsh Society of Edmonton. His heritage. He’s also worked at the YouthWrite arts camp for the last 21 years.

“Be a good human being,” Spyder says on being a successful working artist, “Do a good job, get the work done before the deadline in case anything has to be changed, and always be open to criticism. It doesn’t bother me at all. One of my students came up to me and said, ‘Um, I don’t really like some of  your drawings in your sketchbook.’ And I said, that’s great, that’s fantastic! Because that’s what art is about, to evoke emotion. You’re not supposed to love all art. If there’s art that pisses you off, that’s good. It created that emotion that came out. That’s why this works so well for kids. It’s an outlet for creativity. I’m not that teacher who says, ‘wait, you made the sky green – that’s not right!’ I say, that’s great! I’ve heard this so many times: ‘I wanted to be an artist, but then somebody told me I wasn’t very good, so I never did it again.’ I’m not that kind of teacher.”

your drawings in your sketchbook.’ And I said, that’s great, that’s fantastic! Because that’s what art is about, to evoke emotion. You’re not supposed to love all art. If there’s art that pisses you off, that’s good. It created that emotion that came out. That’s why this works so well for kids. It’s an outlet for creativity. I’m not that teacher who says, ‘wait, you made the sky green – that’s not right!’ I say, that’s great! I’ve heard this so many times: ‘I wanted to be an artist, but then somebody told me I wasn’t very good, so I never did it again.’ I’m not that kind of teacher.”

He’s passionate about his topic, “Art is a very important part of our society, the creativity part. Even if you’re not into art, if you learn how to be creative you can extend that to other things – like science. Maybe you’ll come up with a new theory.”

In 2013, Spyder suffered a stroke that affected his vision. He lost 60% sight in his right eye, 40% in the left, which is why he can’t drive anymore – and he worried his life as an artist would be over. “The first thing I did in the emergency ward was ask my girlfriend for a sketchpad,” he says. “That was the first thing I had to find out: Can I draw? So I drew a little picture and I said, fine, good, I can draw. I don’t care about anything else.”

Spyder seems perfectly fine in a recent interview during his coffee break from his gig with the Art Gallery of Alberta. His manner betrays little anxiety, yet he says things like “it’s a struggle to go to work every day, but I’ve got to do it,” and “I’m always on edge, my anxiety, my emotions are always at 11.” Always with the always. But then he laughs about it. Spyder has a healthy sense of humour to go with that spider tattoo in the middle of his forehead (which briefly freaked out the administrators of a Catholic school where he once taught; the kids loved the tattoos).

Tin foil and masking tape: A favourite craft with Spyder’s students

Spyder doesn’t draw too many gig posters anymore. Part of it is how cheap and easy it is for promoters to knock out designs on computer. Everyone’s an artist. Another part of it is that maybe artists need agents, or at least advocates.

Asked if he’s softened with age, that maybe he’s into bluegrass now, what with the big guitars and all, the 54-year-old artist stands firm. He remains politically active (minus fistfights with white supremacists on Jasper Avenue), he refuses to get a TV or a cell phone, and still listens to Motorhead or Black Flag to get him going in the morning.

He says, “As I like to say, I’m a lifer. My ethics and attitude are the same as they used to be. I have a very strong political background from my dad’s political cartoons, and my politics went to anarchism, which means peace and love and cooperation. People think it’s all chaos and destroy, but it isn’t. We do so many things that are the ideal of anarchism, like the farmer’s market. It’s doing things yourself – and that was the one thing I liked about punk. If it’s not there, do it yourself! If it hasn’t been made, then make it!”

Consider it made.

Top photo by Anna Somerville

One Response to Punk artist reveals deep roots