INTERVIEW: Eamon McGrath imagines ‘Maritime Gothic’

Posted on June 20, 2018 By Mike Ross Entertainment, Front Slider, Music, music

It’s tempting to think that This Town Dies When Festival Season Ends is a song about Edmonton – seeing as songwriter Eamon McGrath was born and raised here.

It’s tempting to think that This Town Dies When Festival Season Ends is a song about Edmonton – seeing as songwriter Eamon McGrath was born and raised here.

You probably think this song is about you, don’t you? But it’s not. We think we have it bad; take a trip to a typical town in the Martimes during the “off-season.”

McGrath, who now lives in Toronto, has played the famous “Sappyfest” in Sackville, N.B., one of the most respected indie rock festivals in Canada – but after that magic first weekend in August, Sackville reverts to what McGrath calls “Maritime Gothic” and the title of his song.

“No one has a job, man,” McGrath says. “There’s no industry there. There’s no opportunity. People start drinking at noon. There’s clothes hanging on the line that have been there for three weeks, and just forgotten about. A white house is about to fall over, all these fishing traps that haven’t been used in 30 years sitting on the lawn. That kind of shit. The Maritimes is dark – and people don’t see that aspect of it.”

He speaks from experience. He plays with New Brunswick’s Julie Doiron, and was hired as Songwriter in Residence at Sappyfest in 2017. He spent a month in Sackville.

“It’s Purgatorial,” he says, “almost like a waiting room – which is a really dark idea to me. The day right after the festival is over, the wristbands blowing in the street, a little bit of garbage left over, maybe someone’s hoodie left behind hanging on a pole, and it’s dark. Everything is closed and a train goes through town and the whistle of the train echoes through everything. You can’t fathom that kind of emptiness. That’s what I was trying to do.”

McGrath says This Town Dies When Festival Season Ends was also written about the suicide of his girlfriend’s mother in 2010. She was from Stratford, Ontario – another city that goes dark once their famous theatre festival is over, he says.

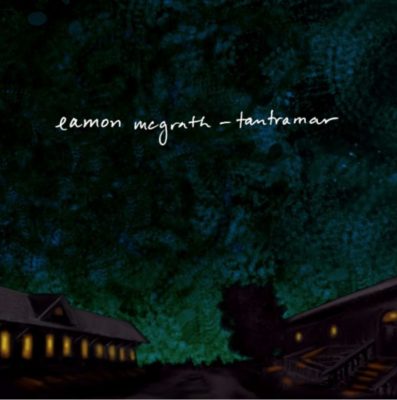

That is just one of many dark songs included on McGrath’s startling new album, Tantramar. Other sample titles: Your Famous Ex-Lover, Never Enough and The World is a Cold Dark Place. Beautiful, haunting and dead slow, it all sounds like an atmospheric fever dream with hints of Nick Cave, Robbie Robertson, Beck, Steve Earle, minimalist, low-fi, nothing over 60 beats per minute, the music filled with sadness and unimaginable emptiness – though apparently he can imagine it. It’s a far cry – literally a far cry – from McGrath’s “punk-turned-folk” Albertan roots.

That is just one of many dark songs included on McGrath’s startling new album, Tantramar. Other sample titles: Your Famous Ex-Lover, Never Enough and The World is a Cold Dark Place. Beautiful, haunting and dead slow, it all sounds like an atmospheric fever dream with hints of Nick Cave, Robbie Robertson, Beck, Steve Earle, minimalist, low-fi, nothing over 60 beats per minute, the music filled with sadness and unimaginable emptiness – though apparently he can imagine it. It’s a far cry – literally a far cry – from McGrath’s “punk-turned-folk” Albertan roots.

He’ll play his hometown release show Saturday afternoon at the Empress Ale House, and sets on the Works outdoor stage next week, with the aptly named “Devastation Trio” – McGrath on guitar and vocals, with upright bassist Tom Murray and pedal steel player Darrek Anderson. No drummer. They just got back from a tour of Europe, where we can imagine they went over like gangbusters in candlelit cavernous German cabarets where people there have lived with darkness for generations.

McGrath has a special connection to the city whose festival season never ends. Edmonton is a great environment for an artist who wants to be honest, he says – simply because no one from outside gives a crap what you do.

“In all the time I was doing this, recording and touring, there was no sense that I was ever going to be successful,” McGrath says. “Just because of the geographical location: You’re never going to be a success. You’re too out of the way. Nobody in Toronto cares about what you’re doing here. Too hard to tour. All that stuff. But I feel I was so committed to being artist; I was demonic to my commitment to making the art I wanted to make.”

Toronto cares what he does now, it must be mentioned – now that he’s developed into this quirky and original artist whose eccentricity seems to be endemic to Edmonton. McGrath is also one of the founders of July Talk (he left in 2012).

He remains “punk” – if not in sound, in spirit. He goes on, “It’s not that Edmonton bands don’t have a sense of ambition. It’s a driving, masochistic ambition, but they have the same kind of ambition someone in Toronto might have but without the concept that you might have to give in to what a record label might tell you to wear. I wanted to figure out how to make a living being a musician, and didn’t see any opportunities for me in anything corporate. So from my first possible moment of playing guitar as an Albertan kid, I knew I was going to have to do it my own way – and that’s something I’ve never been able to let go of.”