REVIEW: Experimental Revolt. She Said. Revolt Again hits the feminist nerve

Posted on November 30, 2019 By Colin MacLean Entertainment, Front Slider, Theatre

Alice Birch’s Revolt. She Said. Revolt Again is an angry and passionate scream railing against the rape culture and violence toward women in general.

Alice Birch’s Revolt. She Said. Revolt Again is an angry and passionate scream railing against the rape culture and violence toward women in general.

The word “feminism” is not mentioned once in the (intermissionless) 90 minutes but it hangs over the production like the sword over Damocles’ head. Birch’s voice is ferocious and unrelenting in advocating that the world must change. And that change should not be in increments – but complete. And right now.

The current production of the experimental 2014 British play is another brave example of Studio Theatre’s policy of pushing at the boundaries of theatrical expression – in its approach to both classic and modern works. The play’s the thing in this demanding production which runs in the Timms Centre for the Arts at the U of A through Dec. 7.

The current production of the experimental 2014 British play is another brave example of Studio Theatre’s policy of pushing at the boundaries of theatrical expression – in its approach to both classic and modern works. The play’s the thing in this demanding production which runs in the Timms Centre for the Arts at the U of A through Dec. 7.

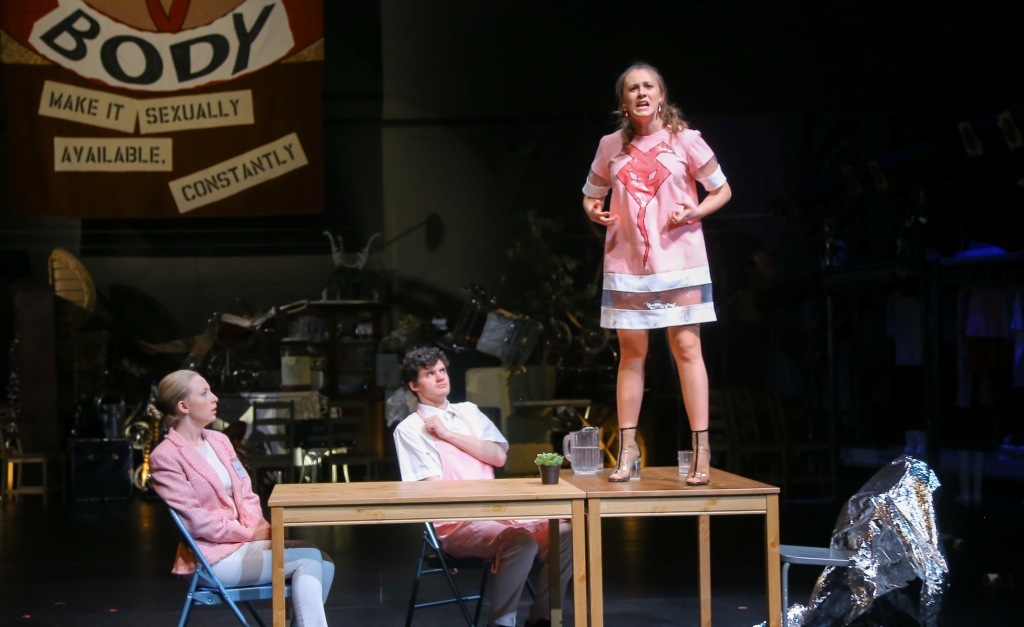

Suzie Martin’s production is set in the vast Studio Theatre stage, where along the sides, set and lighting designer Jeremy Gordaneer has created an attic of clutter from lives lived (mostly female: ovens, clothes lines, washing machines, carriages, etc.). The play is really a series of loaded anecdotes, monologues or sometimes just disconnected sentences playing with language and structure and regarding life in a cynical, existential manner.

Its impact may remind you of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring – strident and atonal. Its power is unmistakable.

The lines between performers and characters are often blurred. They are not a family but they are all sisters – well, except for one poor fellow who, I guess represents all of mankind. It is not clear whether certain characters recur during the play, but the ruling dynamic here is miscommunication, meaning and control. Martin’s bold and insightful direction takes full advantage of the message implicit in the text. The staging is very creative and it’s hard to tell where the writer leaves off and the director begins. The director attacks the play in an urgent, brisk manner pounding home the playwright’s challenging intellectual and storm-the-gates approach while demanding much from her audience. One area where Martin excels is directing her five marvellous actors. Birch often writes her dialogue in bits and pieces while all five – Holly Wandler, Kael Wynn, Meegan Sweet, Kaeley Jade Wiebe, and Christina Nguyen – play characters in extremis, saying the words as if they naturally speak in that manner. There are no words uttered without some kind of mooring in intellect or emotion. Between scenes, actors rush about the stage at great speed, building instant sets out of the detritus around the edges.

Most of the characters do not have names. We know them only from their dialogue. It begins with a man (Wynn) and a woman (Wandler) talking explicitly of their erotic fantasies. Their conversation seems passionate enough as they describe what they would like to do to (or with) each other. The woman takes up a dominant way of expressing herself in graphic sexual terms, leaving the man almost speechless and unsure how to react. As the interaction continues, the fulcrum of power shifts from one to the other. The vignette is very funny and the dialogue full of verbal surprises. It certainly underlines how language has changed since the coming of #MeToo.

Most of the characters do not have names. We know them only from their dialogue. It begins with a man (Wynn) and a woman (Wandler) talking explicitly of their erotic fantasies. Their conversation seems passionate enough as they describe what they would like to do to (or with) each other. The woman takes up a dominant way of expressing herself in graphic sexual terms, leaving the man almost speechless and unsure how to react. As the interaction continues, the fulcrum of power shifts from one to the other. The vignette is very funny and the dialogue full of verbal surprises. It certainly underlines how language has changed since the coming of #MeToo.

Another vignette deals with motherhood. There is grandma who is visited by her daughter and obviously distressed grand-daughter. The daughter accuses her mother of abandoning her because the child was the result of a brutal and abusive relationship. The audience cannot know whether this actually is the truth or whether it is just the daughter’s twisted and surreal explanation of something she cannot understand. It ends in an unexpectedly brutal and bloody manner.

Birch’s wildly theatrical scenes teem with searing humour and drastic acts of defiance. Language is at the core of much of it and the playwright warps and wrenches her biting dialogue while probing gender bias in the way we speak. With costumes and set design by Camille Paris, a host of characters tackle every aspect of contemporary womanhood – often in an existential punk rock scream of rage. A series of banners demand we revolutionize the world – “Do not marry/Don’t reproduce/ Revolutionize Language/Invert it. Birch’s blast furnace offers no answers – suggesting that it’s too late for that.

At the end of the play, in complete darkness, the voice of a woman declares, “Who knew that life could be so awful.” It’s not a question. It’s a statement.

Photos by Ed Ellis