REVIEW: Silent Sky Showcases Struggles of the Sisters of Science

Posted on October 3, 2019 By Colin MacLean Entertainment, entertainment, Front Slider, Theatre

They even have a name for it. It’s called the “Matilda Effect” – coined in 2013 in a report stating that scientific research papers by men were regarded as stronger than those by women.

They even have a name for it. It’s called the “Matilda Effect” – coined in 2013 in a report stating that scientific research papers by men were regarded as stronger than those by women.

The long, sad story of women in science who were ignored, had their findings stolen by others (physicist Lise Meitner) or were just parked in the background and forgotten (Hidden Figures) is a dreary commentary.

Lauren Gunderson was one of America’s least known but most produced playwrights in 2017– her best known play is the hugely popular Miss Bennett: Christmas at Pamberley. Her Silent Sky is playing at the Walterdale Theatre until Oct. 12 to begin our premier amateur theatre’s 61st season. It tells the true story of early 20th century astronomer Henrietta Leavitt, who through sheer grit and a brilliant mind pushed herself from a rural background to work as a “human computer” in the Harvard Observatory. She may have been good enough to do the grunt work in measuring the stars but, being a woman, she was not actually allowed to look into the mighty telescope.

Her arduous journey is dramatic stuff, but Silent Sky seeks to entertain as well in this Kim Mattice Wanat-directed production. There is more here than measuring the cosmos – Leavitt was the first person to measure the universe. Gunderson has penned a life-affirming humanistic play. Her themes are universal: family, the persistence of wonder, and the pursuit of the impossible dream. It is also very funny, both in her view of the battling sisters who are the two main characters, and in the droll and colourful supporting players she surrounds them with.

Henrietta (Lauren Hughes) and her sister Margaret (Joy van de Ligt) grow up in rural Wisconsin. Margaret is content to read her Bible, get married and settle. Her heaven is defined by scripture – while Henrietta’s is as boundless as the universe. The eternal yin and yang gives Gunderson the opportunity to examine the cosmic differences between faith and science and, in perhaps a more prosaic way, the struggle between career and family.

Henrietta (Lauren Hughes) and her sister Margaret (Joy van de Ligt) grow up in rural Wisconsin. Margaret is content to read her Bible, get married and settle. Her heaven is defined by scripture – while Henrietta’s is as boundless as the universe. The eternal yin and yang gives Gunderson the opportunity to examine the cosmic differences between faith and science and, in perhaps a more prosaic way, the struggle between career and family.

The play shows how the two, the very definition of opposites attracting, manage to maintain their loving relationship.

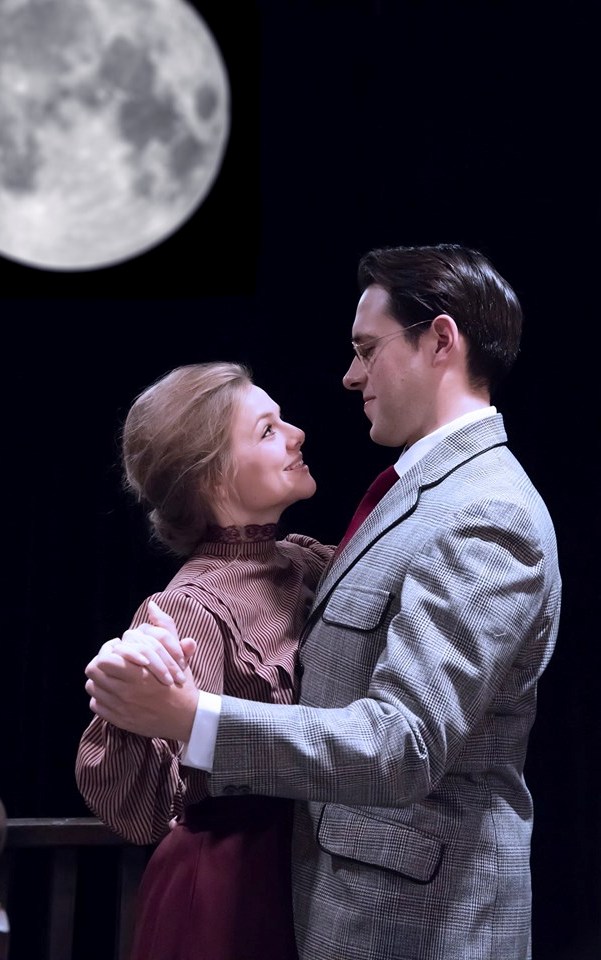

Henrietta the scrappy proto-astronomer encounters sexism – even hostility in the scientific world. Mostly from her obstinate teammate Oeter Shaw (Matt Mihilewicz), who refuses to acknowledge her as a colleague, telling her, “You work for me.”

The two actors, recently married to each other (which may help to explain the on-stage chemistry), immediately establish a prickly-charming relationship that grows when he delivers a lecture in which his view of the universe is painfully limited, much to her horror. Shaw plays the obligatory role of the unbending authority figure, but the canny actor, awkward, geeky and impossibly shy, moves from hard-ass chauvinist to enthusiastic supporter.

Henrietta, who spends her dowry to journey to Harvard, joins two other “human computers” Williamina (Susanne Ritchie) and Annie (Samantha Woolsey), the sniping Statler and Waldorf of astronomy who, although being recognized as brilliant in their field, do not question their place as women in a male-dominated world – however they find themselves drawn to Henrietta’s feisty ways. The three create a supple, humorous and downright endearing trio as they follow small dots of light in the glass negative plates they are given to study. The results of their work to chart the heavens will forever change our view of the cosmos.

As Henrietta, Hughes commands the stage. What a presence this fine actress brings throughout the play as she exudes a ferocious fascination with the stars. She may be a nerdy scientist, focussed on Newton, Kepler and the luminosity of Cepheid variables, but Gunderson proves herself to be something of a poet of the night skies, and gifts the character some high-flying and poetic words.

Upon arriving at the observatory Henrietta breaths, “I’m finally here after a long time of being nowhere.”

The second half of the play runs out of creative spark but pulls itself up with an ending (with the help of Lighting Designer Beyata Hackborn and hundreds of globular lights) that transports the performers, and the entire audience, into a kind of lustrous transcendence.

You will laugh a lot, learn quite a bit and leave with a burnished sense of wonder.